The seventy-sixth Worldcon ends today (and boy are my arms tired). If you’re reading this before noon and you’re anywhere near San Jose, you may still have time to make it to my reading in 211A of the Convention Center. If not, oh well. As you probably suspect, I’m writing this post before the convention has even begun, so I can’t yet give you my take on all the amazing things that happened there, nothing about the surprising upset at the Hugos, nor the author who said that thing that has already polarized our community, nor even the rumor that the most serene republic of san marino is staging a coup to take over next year’s convention in Dublin. Sorry, no spoilers.

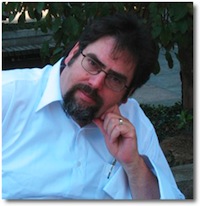

What I can tell you is that this week here on EATING AUTHORS we have another Canadian writer, Omar El Akkad, who, like last week’s guest, is a finalist for the 2018 Sunburst Awards for Excellence in Canadian Literature of the Fantastic.

He was born in Cairo, Egypt and grew up in Doha, Qatar, moving to Canada in his teens. As a journalist he’s covered the War in Afghanistan, military trials at Guantanamo Bay, the the Arab Spring in Egypt, and the Black Lives Matter protests in Ferguson, MO.

American War is Omar’s first novel. Odds are good that if you like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, you’ll enjoy this debut.

LMS: Welcome, Omar. Amidst all your travels, what lingers as your most memorable meal?

OEA: I was born in Cairo. I left when I was a child, but the vast majority of my extended family still lives in Egypt. I go back every few years – to see my relatives, to report on the myriad political and social calamities in which the country seems perpetually embroiled, and to visit my father’s grave in the El Akkad mausoleum within the City of the Dead. Like many immigrants, my relationship with my homeland is one of negative space – I feel a kind of unbelonging everywhere I go, but I feel safest in my unbelonging here.

I remember one night, about ten years ago, my cousins took me out to dinner in a restaurant that, for most of the day, doesn’t exist. I was in Egypt on assignment for my newspaper, working on a story about the wild fluctuations of the country’s burgeoning stock market. I was the one who had pitched the story and yet I was now growing sick of it, sick of the fact that I had come all the way to this place that lives in my marrow only to write a throwaway article about such a quintessentially Western phenomenon – a stupid institutionalized greed whose hallmarks were no different here than in London or New York or anywhere else. I asked my cousins to take me to the most Egyptian place they could think of.

That night they drove me to a wide downtown street, its lanes separated down the middle by a tree-lined median. Old buildings towered over both sides of the street, their bottom floors occupied exclusively by small shops whose signage projected a cascade of gaudy neon into the evening.

But the street itself was empty – no car traffic of any kind. On either side of a two-block stretch, a group of boys and men had just barricaded the intersection. I watched as dozens of people began dragging wooden chairs and tables into the newly made clearing, turning the street into a makeshift restaurant. I couldn’t tell if the people doing this work were employees, volunteers, or folks who were simply walking by and decided to lend a hand. Cairo is the sort of place where, if you look even remotely in need of assistance, half the city will come to your aid. There is no quicker way to make ten new friends in Egypt than to ask one Egyptian for directions.

My cousins and I sat at one of the tables. A few seconds later, a kid came over to take our order. There was no menu, no expectation we would not know exactly what it is we wanted. After all, the place only served one thing – an Arabic dish called Foul (pronounced “Foolâ€). It’s a dish composed of fava beans, olive oil, diced onions, tomatoes, maybe some lemon juice. In much of the country it is breakfast food: cheap, utilitarian fuel that has been a staple here forever. Poor-people food that, like all poor-people food, is eaten by everyone. With the exception of a gilded kleptocracy and an all-but-vanished middle class, Egyptians wrestle constantly with poverty, and poverty produces food that lasts.

In less than a minute there was no more space on our table. Out came the bowls – this one in the style of the Cairenes, that one cooked the way Alexandrians like it. Plates of pickled beets, carrots and turnips, an endless parade of Arabic bread that doubled as cutlery. In the raucous expanse of this street turned dining room, I ate until I couldn’t breathe.

These are the meals I remember, moments of communion with a culture and a history and a people that are at once mine and distant from me. Food is the most effortless vessel of memory, and to break bread is to eradicate exile.

Thanks, Omar. A little more political than the meals I usually see here, but certainly compelling. Timeless food, to be sure.

Next Monday: Another author and another meal!

Want to never miss an installment of EATING AUTHORS?

Click this link and sign up for a weekly email to bring you here as soon as they post.

#SFWApro