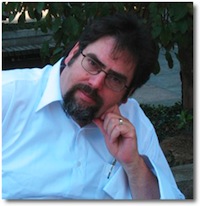

My thanks to the many people who have reached out to me via phone and text and email and social media responses to share their stories, express their support, and offer their positive energies as I begin the journey of medical travails routinely associated with a cancer diagnosis.

I’m currently in limbo as I await the results of a biopsy performed last Tuesday (and I’m still a bit sore from it as I type this up). Once the results are in, I’m expecting a flurry of activity which may include radiation and/or chemo-therapies, as well as surgery to alleviate the stress on my femur and the current pain.

But enough about me, I want to tell you about Kali Wallace, this week’s EATING AUTHORS guest, because I think you need to go out and pick up a copy of her new book (released just last month), Salvation Day. It’s gritty, it’s real, it’s an SF thriller with cultists and a spaceship full of death and if this book doesn’t end up on the big screen from a major studio then there is no hope for humanity. So, yeah, pick this up.

As for Kali herself, she’s a transplanted Coloradoan now living in southern California. She’s a Clarion graduate and holds a doctorate in geophysics, having done research on Himalayan mountain-building and Indian earthquakes (as one does).

And she’s been busy with fiction, making a solid name for herself with short stories in such venues as Lightspeed, Tor.com, Clarkesworld, F&SF, and Asimov’s. And then there are her two YA novels. If you’ve not read any of her stuff, then remember you heard about her here first, because I suspect you’ll be hearing a lot more, everywhere.

LMS: Welcome, Kali. Please tell me about your most memorable meal.

KW: About fifteen years ago, when I was a couple of years into my PhD program, I traveled to western China to do some field work. My research was in geophysics, and for this trip my goal was to measure the motion on a massive strike-slip fault that slices across the northern edge of Tibet. I did this by using GPS to remeasure the precise locations of survey points installed by a colleague a few years before–and what that meant, practically, was that I spent a few weeks driving around the so-called Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region with a Chinese scientist, tracing a branch of the ancient Silk Road along the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert.

Xinjiang is a huge and beautiful place, with towering mountains, vast deserts, ancient market cities, remote mountain villages, and modern industrial towns built and run by the Chinese government. And everywhere–in the signs, the languages, the faces–everywhere there is a visible clash between Han and Uyghur cultures.

The last part of our field work took us away from the desert and into the Altyn Tagh Mountains, the long, curving range that forms the northern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. After two days on rough roads, which included one very exciting ford of a river that was much deeper than we ought to have risked, and three nights spent in smaller and smaller Uyghur villages, we loaded up about half a dozen donkeys with our GPS equipment and ourselves and headed into the mountains.

It was a cold, rainy day as we climbed through a narrow, rocky canyon marked by churning rapids and banks of crusty snow. About midday we crested a 4000-meter pass and descended into a breathtaking river valley so open and wide it felt like we had stepped into another world. We saw nobody, but my Chinese colleague, passing along reassurances from our Uyghur guides, told me there were people living up here, people we could stay with for the few days it would take us to collect our data. I had my doubts, exacerbated by not one but two language barriers, and those doubts grew into fear when the guides admitted the people were not where they expected them to be. It was growing dark by the time we spotted in the distance two white tents, a small fire, and a scattered herd of goats.

The Uyghur family was not expecting us; they were a solid day’s travel from any other humans and likely never expected visits from strangers. A man, his two adult sons, and the wife of one son were all living in two large tents on a flat area between a river and a jagged line of mountains. This was where they brought their herd of goats to graze in summer. I have no idea what my Chinese colleague and our guide told them–usually the shorthand was to simply say we studied earthquakes and leave it at that–but they welcomed us into their home in spite of our sudden intrusion.

They slaughtered one of their goats for dinner, and in the larger of the two tents we crowded around a smoky but blissfully warm fire to eat salty, greasy, sizzling chunks of meat with pieces of dried flatbread softened in cups of hot tea. I was exhausted, frustrated, saddle-sore, tearing up from the smoke, and two languages removed from being able to speak directly to our hosts, yet that meal of meat, bread, and tea was one of the most delicious and satisfying I’ve ever had in my life.

At one point, the father brought out a wireless radio and switched it on. He spent some time fiddling with the AM stations until he found one that came in clearly. The voice on the radio was speaking Russian–which seemed odd to me, but it wasn’t like there was a lot of choice–but when he gestured to me and said something, my Chinese colleague laughed. He explained that the man had picked the radio station for me. In that part of the world they assumed, naturally, that a random white person who showed up at their mountain camp would be Russian. When he explained to our hosts that I was American, they found an English language station on the radio: the broadcast of a terribly earnest Christian Science program based in Mumbai, well over a thousand miles away across both Tibet and the Himalayas. They had no idea why the unexpected topic of the broadcast amused me, and I had no idea how to explain.

I thanked them for thinking of me, for giving us food and shelter, and I hoped they understood, in the twice-translated passage of my awkward words, that what I was really thanking them for was being the light I’d spotted at twilight just when the world seemed distressingly empty, for opening their home to strangers who couldn’t even speak their language, for being a warm sanctuary on a cold, dark night.

My colleague and I slept in the other tent–I think we took the married couple’s place–comfortably sandwiched between layers of the thick, colorful, woolly quilts that every Uyghur household has in abundance. I was worried that I would have trouble sleeping, as it was such a strange and remote place, and I had so much anxiety about what was ahead, but I drifted off at once and slept through the night.

I woke to cold gray morning light and saw what I had not been able to see in the dark: right next to where I’d folded my sweater as a pillow, wrapped up in a plastic bag, was the severed head of the little goat we’d eaten the night before. I was too groggy to be revolted, so I just blinked at it in confusion, eventually mumbled a good morning for no reason other than that it seemed like I ought to say something, and stepped out of the tent to watch the sun rise over the mountains.

Thanks, Kali. There’s an important lesson here about reframing: when waking up in a strange place and finding a severed goat’s head nearby, rather than freaking out about it, be grateful that it’s been wrapped up in plastic.

Next Monday: Another author and another meal!

Want to never miss an installment of EATING AUTHORS?

Click this link and sign up for a weekly email to bring you here as soon as they post.

#SFWApro

Tags: Eating Authors