I’m still shaking off the travel fatigue from the excesses of 2016. Don’t get me wrong, last month’s two conventions (the GOH gig at VancouFur and the Roastermaster spot at Albacon) were glorious but I’ve been really happy having no travel obligations this month, allowing me to focus on matters closer to home like health and family and writing. I suspect these are priorities that most of you can appreciate.

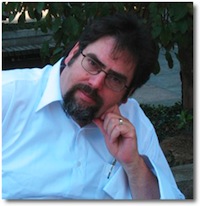

And speaking of things to appreciate (see what I did there?), it’s time once again for me to shill for this year’s Campbell Award nominees. Last week Sarah Gailey dropped in to share her most memorable meal. And as has been previously noted, Ada Palmer did the same back in May. In two weeks time I plan to share Kelly Robson‘s recollections on her meal, and with some luck I’ll have answers from J. Mulrooney and Laurie Penny as well. But for now let’s focus on today’s EATING AUTHORS guest, the fabulous Malka Older.

Malka first novel, Infomocracy topped the charts of Kirkus‘s Best Fiction of 2016, and the Washington Post dubbed it one of the best science fiction and fantasy novels of 2016. And this book was just the beginning of her Centenal Cycle series, with book two, Null States, due this September.

But as incredible as her fiction is, her nonfiction life stikes me as just as powerful. Malka is a humanitarian worker. In 2015 she was named a Senior Fellow for Technology and Risk at the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs. She’s worked in humanitarian aid and development, specializing in disaster and post-disaster issues in places including Darfur, Japan, Indonesia, Mali, Sri Lanka, and Uganda. Right about now she’s finishing up her Ph.D. at the Centre de Sociologie des Organisations where she’s been studying governance and disasters.

LMS: Welcome, Malka. What stands out for you as your most memorable meal?

MO: It took me a while to figure out what to write for this. First of all, I hate superlatives in general – “who is your favorite author?” may be my least favorite interview question. Then, I’ve had so many amazing meals. Should I write about the fried scorpions in the Beijing street market? The grilled river snake on the banks of the Tong Le Sap? The fish eaten minutes after it was caught on a fishing platform in Maluku?

But what I kept coming back to was something not extraordinary at all. It was not even one meal, but an amalgamation of many. It was also not just the eating, but the whole process of entering a calming sanctuary, selecting from an impossible range of items, and unwrapping to eat. It was comfort food, strange new options, and perfect service. I’m referring, of course, to Japanese convenience store meals.

Convenience stores are everywhere in Japan, and from them you can buy anything from socks to stationary. You can use the bathroom without making a purchase, ship your suitcase home if you don’t want the bother of carrying it, make a photocopy. You can buy ramen and they will add the hot water, buy a pre-made meal and they will microwave it for you, or you can select what you want from a range of vegetables and starches bubbling on a constant simmer by the cash register and they will serve them to you in a take-away container with a helping of broth and a smear of super-spicy mustard.

I ate from convenience stores pretty regularly when I first lived in Japan. I was in a rural area and spent a lot of time in my car, so convenience stores were my oases. But now my memories of コンビニ御飯, as it’s known, are tied to the time after the 2011 tsunami that devastated the northeast coast of Japan.

I arrived in Tokyo around a week after the disaster, and other then the blinking red “empty” lights on the drink vending machine in the airport, a convenience store was the first indication I saw of the disruption. I had arrived late at night and exhausted, and so my obvious move after checking into the hotel was to find a convenience store to grab some quick snacks rather than dealing with a restaurant. I walked down some quiet clean streets to a main drag following instructions from the hotel, but when I arrived I was shocked to find empty patches on the shelves, adorned with – and this might have been more shocking still – hand-lettered signs apologizing for the inconvenience.

The rest of Tokyo seemed to be functioning more or less normally – the just-in-time delivery systems of the convenience stores had, for once, not worked in their favor – but when I got up north a few days later it was a different story. In the towns where we were working there was often nothing left, just piles of rubble and roof-tiles and hastily cleared roads, and in the towns that were only partially destroyed nothing was open. Normal life had been stripped away by the waves. Everyone was in mourning or in emergency mode, or both.

Since there was obviously nowhere to eat, let alone stay, in the affected area, we slept in a town about an hour’s drive inland. Even there, unhit by the tsunami, the earthquake had caused blackouts and some minor infrastructure damage, and when my colleagues first arrived the only restaurant open served the local delicacy of grilled entrails. (I’ve tried it, and it’s probably not as bad as you imagine, but there’s nothing delicate about it). By the time I got there more options were opening up, and our long days in the field were usually capped with boozy, complicated, long, and communal izakaya meals, but to fortify ourselves during the day our first stop was invariably a convenience store. We would stock up on snacks and portable meal components, each person to their taste, and refuel gradually throughout the day during the drives past long stretches of farmland and of debris, and the searching for alternate routes when our GPS, not yet updated for the disaster, failed us.

As economic activity started to revive in the affected towns, chain convenience stores – backed as they were by powerful corporations – were some of the first shops to reopen. They set up temporary buildings, flimsy prefab on the outside, but on the inside they looked just like convenience stories anywhere in Japan: bright, even fluorescent lighting; shelves lined with the colorful labels of dozens of instant ramen brands and tiny trays of shrink-wrapped pickled vegetables; freezers stocked with every imaginable variety of tea, along with coffee, juice, soda, and drinkable yogurt. It made days in the field much easier: at least we knew there was a place we could stop, even if it was just to use the bathroom – although that, in some of the temporary convenience stores, might be a portapotty.

Eventually the frenzy of late night drinking and camaraderie wore off. Between exhaustion and the slow, reluctant return to some kind of normalcy we were all realizing that we couldn’t feast and get drunk every night. I enjoyed the izakaya nights, but I didn’t mind the change. When I look back on those meals I have an impression of strange and delicious food, ordered en masse and eaten family style. I remember laughter, sometimes grim and sometimes raucous, and I remember toast after toast with beer and sake, but I find it difficult to capture specific episodes (although that could be because of the sake).

Instead I remember walking home alone on dark, quiet streets. I would stop by a convenience store on the way for a plastic bag of neatly wrapped foodstuffs and carry back them back to eat alone in my tiny hotel room. After the days of looking at destruction in the field, the evenings of paperwork in the office, eating alone felt like a kind of sanctuary, a sanctuary centered around the calm, glowing certainty of convenience store food.

I remember walking the immaculate aisles, ostensibly to scan for overlooked goodies or new seasonal treats, although the real reason had more to do with soaking up the feeling of normal, clean, ordered life, demonstrated through the easy availability of an exemplary range of consumer products. I was partial to senbei rice crackers, and I tried all different kinds: puffy deep fried, soy sauce marinated, speckled with dry beans. I made an effort to eat some kind of vegetable: pickled daikon, or kimchi, sitting in a tiny cardboard tray and tight-wrapped in plastic. For dessert I picked a large cookie, wrapped in its pink-printed plastic: caramel or white chocolate chip.

But the centerpiece was always the onigiri, thick triangles of rice with some kind of filling, the basic unit of a Japanese take-away meal. I picked two or three, pickled plums or marinated seaweed or a slice of grilled salmon. Back in my hotel room I peeled off the sequential tabs: #1 bisecting the wrapper from the top angle and #2 and #3 pulling away from each corner, carefully so as not to dislodge the folds of nori. And then I would take the first mouthful of rice.

Every time I took that first bite, I remembered the scene in åƒã¨åƒå°‹ã®ç¥žéš ã— (Spirited Away) when Sen – whose reality has fallen away so desperately that she no longer has a name – is given an onigiri as a tiny, insufficient morsel of comfort. She takes a bite, and you can almost taste the rice, plain and starchy and sustaining. The tears start to run down Sen’s cheeks. She takes another bite, and another, stuffing the rest of the rice into her mouth, and the food lets her finally cry.

Thanks, Malka. The miracles of convenience stores in Tokyo and Yokohama are some of my best memories of Japan, from endless and mysterious varieties of “meat on a stick” to those perfect hardboiled eggs that were somehow salted inside the shell.

Next Monday: Another author and another meal!

#SFWApro

Tags: Eating Authors

I really liked this. Thanks!

04.24.17 at 9:19 am