November is winding down and time is speeding up. If you’re reading this on the day it posted, then I’ve just returned from a convention, the Thanksgiving holiday is just a few days off, and another convention lies just the other side of it. Despite the convention bookends, I’ll be spending this week in serious reflection of all the things I have to be thankful for this year.

Not least among them (he said in his best segueing voice) has been knowing this week’s EATING AUTHORS guest, Michael Livingston. Back in May of 2006, there was some serious discussion among members of Codex — an online community of authors — who had just returned from that year’s Nebula Awards Weekend. That conversation inspired my decision to edit a reprint anthology featuring some of the best work by Codex members and I announced my intention to the community with a call for submissions. Soon after, Mike contacted me, letting me know he’d been thinking along similar lines and I’d beaten him to the punch. My response was to offer to share the project with him, and he went on to become my co-editor for Prime Codex, as well as another project when that first book turned into my small press, Paper Golem.

Mike and I share other a few other similarities, both of us working as authors and editors and academicians, but we quickly diverge paths. He’s won the celebrated Writers of the Future contest, is an active outdoorsman, appears to have a disturbing amount of automotive knowledge (at least relative to me), and has a talent for making history live and breathe that I cannot adequately describe with a paltry word like “envy,” but there you have it.

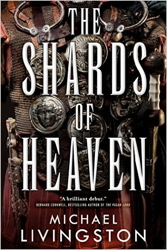

I’m delighted to tell you that his first novel, The Shards of Heaven, comes out tomorrow from Tor Books, but even more that it’s but the first book of a trilogy. Because, as well all know, history repeats itself (sorry, I tried to edit that last bit out, and failed).

LMS: Welcome, Mike. I’m so happy to have you here. So, let’s talk memorable meals!

ML: The finest meals to me are memories — not just of the items in the table, but also of the people around it. So while I could talk about the occasional extraordinary culinary delight, I could also easily point to raucous family meals from my childhood, campfire cookouts in the Rockies, or even pizza-on-paper plates meals while rolling 20-sided dice with my friends.

So perhaps I’ll talk about something that’s a little of all that.

In my day job I’m a college professor, and I specialize in the study of the Middle Ages. It was this hat that I was wearing in the summer of 2014, when I traveled to northern France with a very good friend and fellow historian, Kelly DeVries.

Over the previous year Kelly and I had been writing a book together on the Battle of Crécy, which was fought in 1346. In the course of this project it had become more and more clear that this battle, which is one of the most famous in history, didn’t happen where everyone said it happened. Between the sources and the terrain and any logical actions on the part of the several kings on the field that day, the Battle of Crécy simply could not have happened where it was traditionally located. Even more that that, I became convinced that I knew where all the evidence was actually leading us.

So that summer Kelly and I went there. We drove our little rental car out to the fields of northern France. We found the site I had located between Napoleonic tax maps and Google’s satellite imagery. We got out of the car, and we walked.

What we found was remarkable, and it truly cemented my theories. Late in the day, Kelly and I stood in a field of wheat where thousands of men had died over six centuries earlier. “Mike, you found it,” my friend said. His voice was a wondrous mix of excitement and pride.

I, too, felt the rush of discovery. But I felt something else, too. “Maybe,” I said. “But if I did, there are only two people in the world right now who know where many thousands of men lost their lives. And we’re standing in the middle of it.”

An hour later we made our way into a small Mom-and-Pop cafe in the town of Saint-Riquier, where we were staying. The evening was calm on the patio. We ordered a bottle of French wine and a couple of dinner crepes.

We sat and talked. The wine was superb. The crepe was simply the best I’ve ever tasted.

The meal truly was objectively magnificent, but I cannot deny that the thrill of the discovery was also upon us, a deep satisfaction of a job well done, a payoff to the sleepless nights of toiling like Gandalf over manuscripts and old books.

One way or another, it made for one of the most memorable meals in my life.

It’s a profound, humbling, and exciting thing, that sense of discovery. I feel it whether I’m engaged with my research as a professor or my writing as an author. There’s a weight of responsibility in what we do. We need to get it right.

One of the things that had driven me to that meal was my belief that the thousands who died in 1346 deserved to have their resting place known.

And it’s one of the things that drove me to write The Shards of Heaven, too. Cleopatra and Augustus Caesar, Juba and Caesarion, Selene and Pullo and Vorenus … they, too, deserve their truth. Whether or not that truth really involved the Trident of Poseidon and the other Shards … well, I guess that remains to be seen!

Thanks, Mike. I confess, one of the things I miss from my days in academia is indeed that moment of insight. Forget what they say about ‘hunger being the best sauce.’ Nothing beats discovery.

Next Monday: Another author and another meal!

#SFWApro

Tags: Eating Authors