If it’s December, then it means I’ve survived the stupidity of doing four conventions in the month of November. I’m expecting this to be a quiet month, where my focus will be on finishing a novel, lowering my weight and blood sugar, and exercising regularly. Today is also the first day of Hanukkah, and for those who celebrate, a hearty Chag Urim Sameach to you. Wow, Kislev sure came early this year. I swear, it seems like only yesterday all the stores were playing traditional Cheshvan music.

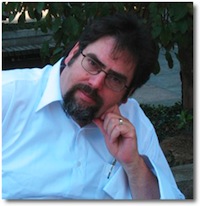

As a writer, I believe that all quality fiction deals with some aspect of the human story. How we struggle with the tribulations of life, how we celebrate our successes, how we treat one another, how we summon the future. That may not seem like a segue to this week’s EATING AUTHORS guest, but in point of fact following S. L. Saboviec‘s account of her battle with cancer (stage 4, metastatic breast cancer) has been both moving and inspirational in ways that most fiction can only aspire to.

She’s a year and a month a few days past her diagnosis, marking her as a survivor. She’s been maintaining a blog of her journey (a bit less regularly than she’d like), and I highly recommend it for anyone who is or knows someone who is dealing with similar straits. Here’s a link.

She’s also written three novels about angels and demons. When time and circumstances allow, when she gets to draw on the experiences of the past year, I have no doubt that her fourth book will set the world afire. Until then, here’s her take on her most memorable meal. It’s awesome.

LMS: Welcome, Samantha, what’s your most memorable meal

SLS: Sixteen years ago, when I was but a young, carefree college student, I had dreams of saving the world. My ideas, back then, were a jarring contrast to those I currently hold, and indeed, at the time, I wouldn’t have even recognized thirty-seven-year-old me. Time and life experience has a tendency to change a person, but even I marvel at the jarring contrast between myself now and myself then.

I would describe myself presently as a liberal, feminist, trying-to-be-woke, supporting-marginalized-people, almost-socialist. Then, I was a conservative, small-town-living, born-again Christian, raised to believe the world needed the message I carried in my heart. This impelled me to go on summer mission trips at 18, 19, and 20; this story concerns the mid-summer after my junior year at Iowa State University.

I, along with about one hundred other students and leaders from across the United States, spent a month in southern Africa. We prepared in Maun, Botswana, camped outside a small village called Nxamasere for the bulk of the trip, and finished up with a couple days in Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe. We built huts, ran a week-long Vacation Bible School for local children, and helped teach locals how to stop the spread of AIDS.

Africa.

Any words I might choose seem overwrought, cliché, or both. It is exactly as you see on TV, only more real, tangible, and beautiful than a picture can convey. Merely seeing the landscape changed me; interacting with the locals sent me on a path toward who I am today.

My most memorable meal happened on the last night we were in Victoria Falls. Our leaders took us to a buffet with a spread of many different kinds of breads, meats, and desserts. I filled my plate with kudu, warthog, and ostrich. My fellow missionaries urged me to try their signature dish: Mopani worm.

I did it. I put the worm in my mouth. I bit into it. It squished apart, and I swallowed it.

I even kept it down.

The meal was a culmination of the whirlwind I’d been through those past few weeks. Yes, people exist who eat insects was a concept that encapsulated my experience. Before then, I knew people like that existed. But I didn’t know know. Eating the worm was as much to solidify the reality in my mind as it was to do something I would not normally do. If I hadn’t eaten it, I was certain, I would regret it for the rest of my life.

But eating a bug wasn’t the most life-changing thing that happened that week. As I sat around the table with the strangers-turned-friends I had made, my thoughts returned to one small occurrence that morphed my entire worldview.

Nxamasere had no electricity. The villagers lived in dung huts and hauled water from one of two wells at opposite ends of their town. My mission group slept in tents about a mile away. One of our projects was to build a latrine for them—with no running water, mind you. Our bathroom was just north of us, a giant sandbox that looked no different from where we pitched our tents.

At night, I sat under the stars and marveled at how brilliant the Milky Way was. Once again, words fail me: we’re all jaded by television and movies, surround sound and IMAX. But something about truly seeing the sky and breathing the African air touched my soul, straightened out my crinkled corners, and gave me new life.

The children who came to the Vacation Bible School ranged in age from three to eighteen. Their skin was obsidian, their hair cut short. They were curious and shy, most of them both at the same time.

During downtime, our translator would allow questions from them to us. They’d heard stories of the Western world, but they’d never been outside their small villages. Where would they go, and how would they get there? As a village, they owned an old jalopy of a car that they would use for emergencies—I never asked where they got gas nor where the car itself came from.

A little boy about seven years old was bursting to ask a question. The translator, who seemed mostly bored by the entire experience, was half-heartedly translating. The boy was bouncing, his hand in the air, so I pointed at him.

He talked animatedly to the translator, who waved a dismissive hand and gave a curt answer in Setswana.

“Wait,†I said before the translator could move on. “What did he say?â€

The boy’s eyes were shining. The translator said, “He wanted to know how many water pumps are in your village.â€

“What?†I answered.

The translator had been there to pick us up at the airport in Johannesburg, South Africa, which was a modern, if extremely foreign-seeming, city. He was clearly not impressed with the wide-eyed naivety of the children. He sighed. “He’s very proud because Nxamasere has two water pumps. Most villages only have one.â€

My mind stalled, and before I could think of how to explain, the translator had moved on to another child.

That was the moment my world opened up.

How do you explain to a proud child that in your house, you had more “water pumps†than all of his surrounding villages combined? One room in our homes has three, including one to flush away waste.

It was such a small and apparently easily-dismissed question. Sixteen years later, I still think of it with wonderment. It isn’t about the technology or the living conditions—it was never about that—it was about how different the world can be. The Batswana I met were happy. They didn’t want to live in the Western world. They didn’t seem to feel that anything was missing in their lives. When I looked at them, I felt something missing. But when they looked at me, I saw curiosity, not longing.

For the first time in my twenty years of life, I realized that the world could never fit my preconceived notions. What I had been taught in subtext was wrong. I didn’t need to go out and force the world to fit into my conservative, small-town-living, born-again Christian beliefs. I didn’t have the word for it at the time, but imperialism irrevocably shattered for me.

The night of the dinner, the culmination of the exotic experiences I was finishing, that memory played over and over with me. It simmered for months. It still simmers.

Such a small, innocent question.

Such world-changing ideas behind it.

Thanks, Samantha. That was some transformational meal. The metaphor that comes to mind is right out of Genesis, only instead of taking a bite out of the apple, you bit into the worm inside that apple.

Next Monday: Another author and another meal!

Want to never miss an installment of EATING AUTHORS?

Click this link and sign up for a weekly email to bring you here as soon as they post.

#SFWApro

Tags: Eating Authors