Last month I was in Los Angeles for the annual Nebula Conference. Without a doubt, the highlight of the week was getting to meet face to face with a writer I’d been introduced to a couple months earlier via first one and then a second Slack channel. We’d really hit it off, though we had very little in common, to the point where we’d begun bouncing off ideas for multiple collaborative novel projects.

I had some real concern that our budding “bromance” was all a product of online chats and would not survive our actual meeting. As it turned out, he had the same worry. In the end, we meshed even better in person. So much so that, despite both of us being stupidly busy with too many other projects, we laid plans for our first collaboration, an epistolary first contact novel based on faulty translation software.

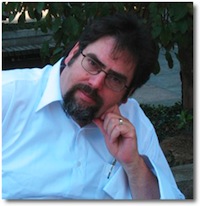

All of the above is by way of introducing this week’s EATING AUTHOR guest, Yudhanjaya Wijeratne. When he’s not writing Nebula-nominated fiction, Yudha applies high level economic and sociological data analysis to political commentary. He’s been a tech journalist, a blogger, a TEDx Speaker. Lately, he’s been responsible for an A.I. poet that writes in old Tang dynasty style (follow the poems on Twitter). Unsurprisingly, his dayjob is at a Think Tank.

He’s currently negotiating foreign sales for several books, fielding movie options, and writing, writing, writing. If you’re not familiar with his work, go out and get it now. This is an author that is going to burn brightly.

LMS: Welcome, Yudha. Talk to me about your most memorable meal.

YW: I’ve never been what you might call a food connoisseur. If I am, it’s as an aficionado of the dark alleys and cheap, late-night stalls. For much of my formative years (2000-2011) we never had much money for food, so whatever instincts I have are fine-tuned to getting the most amount of fried rice per rupee. There was a certain science to it – if you found a place just the right distance away from a junction, and hit it about twenty minutes before lunchtime, you’d get a generously mangled knock-off fried rice that was neither Chinese nor Sri Lankan but some generic Asian lovechild born from the cheapest possible components of both.

And you could pay twenty rupees more for a polythene bag full of the horribly oily chilli paste you found only in shops like that; the chilli paste set your mouth on fire and slowed down the eating so you ended up rationing out of reflex, rather than any conscious choice. A good “full buth packetâ€, laced thus with enough chilli could feed two of us, or last two meals for one.

My family never connected over these meals – we ate in silence, as apart from each other as possible. My mother would watch the TV, my father would sit outside the house with a cigarette pack ready, and I would stare at yet another half-finished manuscript on the clunky secondhand Pentium II computer I’d bought. That blinking cursor and those cheap, fiery meals became as much a part of my identity as anything else.

My most memorable meal was somewhere in 2015. I was in London, in Piccadilly Circus, and I was miserable.

On paper, I was doing fine. I had left poverty behind; in fact, I had a very cushy job and a very startup-ish company; they paid me far more than people my age made – and with the job came plenty of international travel. I had rented a proper house for myself and my mother, and I could afford whatever I wanted, three meals a day. I knew that all I had to do was hang on – do my duty, do it well, and eventually all the things I never dared dream of might be mine. Long before I hit thirty.

But this comfort came at the expense of my identity. Not just as a writer, but as a person. These aspirations weren’t mine; these social clubs weren’t what I was built for. I stumbled around like a drunk – or worse, someone who’d woken up in a skin-suit not his own and was fumbling around with the controls. The conference I had come here for was done, the company so gratingly competitive that I’d left them behind and traded the fancy hotel room for cheap lodgings in Tottenham. I’d bought fish and chips, only to discover that the British preferred their food to taste like soggy cardboard.

So I sat there in the gray rain with tasteless fish and my oversized backpack and watched a man scrawl a poem from one pavement to another, building a zebra crossing made of politics and prose. Right next to me a man was selling drugs to a group of inebriated women from a hen party. I wondered, not for the first time in my life, why I should bother waking up the next morning. Surely it was easier to fall back into the old pattern, the quick vertical cut down the right wrist; and this time, unlike the last, I would do the job right, instead of just cutting slightly to the left of the vein.

Somewhere inside me the buth-packet-seeker woke. I passed the fish on to someone who needed it more and began walking.

I can’t tell you how long I walked for – it might have been only fifteen or thirty minutes, but it felt like a cross between an eternity and no time at all. Something led me to the side alleys and the places that well-dressed people skirted around. And at last I stood before my Grail: a cheap restaurant that smacked of the kind of generic Asianness that I knew well. And there I found a fried rice that was cheap, and asked for more chilli paste than the waiters were comfortable serving me, and I ate like I hadn’t seen food in years.

Outside, two drunks started whacking each other. One of them had a cricket bat, which I later hefted as it lay on the pavement: good English Willow, heavy, the kind of thing you want on your side in a fight. But right then I paid them no heed. I ate until I could barely move and I was bleeding chilli tears from the paste and the waiter had warned me I might get ulcers if I ate more chilli. I didn’t care. I pulled out my laptop and stared at the manuscript I’d abandoned when I joined the company. I decided right there that I would finish this thing, no matter how many cheap rices it took.

For better or for worse, I was back in my own skin. And if I wasn’t happy – well, at least I had a reason to get up the next morning.

Thanks, Yudha. Forever after, I fear I will find myself assessing my meals by asking if there’s a drunk with a cricket bat nearby.

Next Monday: Another author and another meal!

Want to never miss an installment of EATING AUTHORS?

Click this link and sign up for a weekly email to bring you here as soon as they post.

#SFWApro

Tags: Eating Authors